|

Labor Day is more than just a summer-ending holiday; it began as a celebration of labor unions and the American labor movement. That’s easy to forget these days because labor unions have lost their central place in the American economy.

At the height of their influence in the mid-20th century, labor unions represented about 1 of every 3 American workers. Today, it’s 1 in 9.

But that shrinking size doesn’t always mean waning influence. Unions have been a major force behind the “fight for $15” movement that’s boosting increase the minimum wage in states and cities across the country.

So even though they’re short on members, American labor unions are still finding ways to wield their organizing influence and help American workers.

Who still belongs to a union?

While union membership has fallen to just 11 percent of US workers, that’s still 14.8 million people — more than twice the population of Massachusetts.

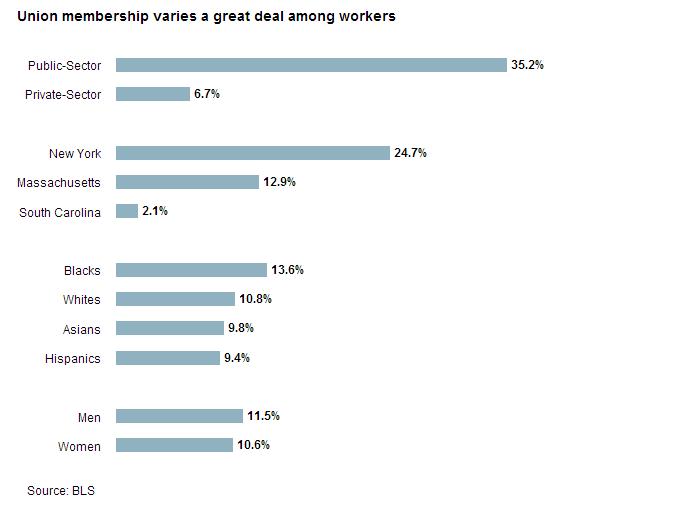

Why has union membership fallen so far?Variations abound when you break the numbers down by race, gender, and geography. There are more union men then union women, and a higher percentage of blacks than whites. Public sector workers are five times more likely to join unions than their private-sector counterparts, and workers in New York are 12 times more likely to do so than workers in South Carolina.

Why has union membership fallen so far?

It’s really a tale of two sectors, the public and the private.

Public-sector unions — meaning those that represent local, state, and federal government employees — have been pretty stable. In 1985, 36 percent of public sector workers were in unions, virtually the same rate we see today.

By contrast, private sector unions have been decimated. Their membership numbers have fallen over 50 percent since 1984, partly in response to globalization and partly as a result of various legal changes that have curtailed unions’ ability to organize.

.JPG)

How have shrinking unions continued to wield influence?

Unions have embraced their role as leading advocates for worker’s causes — even when the workers aren’t actually union members.

The “fight for $15” movement began as an effort to help boost the wages of fast food workers in New York, few of whom belonged to unions. And as it has spread across the countries, fight for $15 has galvanized progressives and worker-rights advocates to a cause tailor-made for the current moment — better wages for hard-working folks left behind in our increasingly unequal society.

So far, two states and a handful of major cities have committed to raising the minimum wage to $15 in the coming years (will Massachusetts be next?). That’s a huge victory for the labor movement, in so far as it will increase the earnings of thousands, or perhaps millions of workers.

But if unions are going to continue serving as the voice of American workers and mobilizing support for far-reaching cause, they need to find a way to attract new dues-paying members.

Does it matter that union membership is in decline?

Unions increase the bargaining power of workers, which translates into higher earnings and a stronger voice for employees.

The big economic critique of unions is that while they may help members, they actually hurt other workers. By interfering with the natural operations of the economy, they push wages above their normal level, heighten inflation, and make it difficult for companies to hire and fire workers as needed.

On the other hand, recent research has traced a direct line between the fall of unions and some of the foremost problems in the US economy, including rising inequality and stagnant wages. Anew report from the Economic Policy Institute estimates that the decline of unions has cost private-sector workers nearly $3,000 per year — even more for non-college grads.

What’s more, the decline of unions may have helped open the doors to rising inequality. As unions have lost power, income has increasingly flowed to the top 10 percent of earners.

|