Source: economist.com

High, and rising

“FOLDING BEIJING”, A short story by Hao Jingfang, a Chinese science-fiction writer, is set in a futuristic version of China’s capital where inequality is so stark that different social groups are not allowed to use the same ground simultaneously. They take turns occupying the area within Beijing’s sixth ring road, which flips over every 24 hours. One side has clear blue skies, tranquil leafy streets and supermarkets with imported food, where the 5m people of “First Space” people enjoy a whole 24 hours, whereas the 75m people of “Second Space” and “Third Space” get only 12 hours each. This last group is crowded together in a place where construction dust obscures the tops of neon-lit buildings and workers toil “for rewards as thin as the wings of cicadas”. People are beaten and imprisoned if they enter a zone above their station. “There are many things in life we can’t change,” says one character. “All we can do is to accept and endure.”

Present-day Beijing resembles Ms Hao’s fiction: you can buy handbags that sell for more than some workers make in a year. The People’s Republic has travelled a long way since it was founded on the dream of equality in 1949. Today it is one of the most unequal societies on Earth.

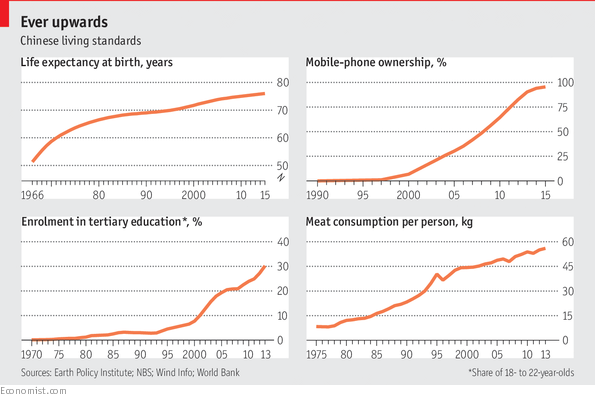

Until the late 1970s owning private property was almost entirely prohibited and very few people had substantial personal assets. The accumulation of wealth since then has been extraordinary. Between 1990 and 2014 income per person in China increased 13-fold in real terms, whereas globally it less than tripled. After Mao Zedong died, Chinese consumers dreamed of buying the “four rounds” (bicycle, sewing machine, washing machine and wrist watch) and “three electrics” (phone, refrigerator and television); these days they are more likely to yearn for sports-utility vehicles and trips to Thailand.

The greatest divide in both income and opportunity is between rural and urban areas. Less than 10% of rural youths go to senior high school, compared with 70% of their urban counterparts. Most rural youngsters leave school at 15, whereas a third of urban ones gain degrees. Within cities the main division is between migrant workers and local residents: most migrants lack the urban residence permit that would give them and their children access to public services such as schools and hospitals.

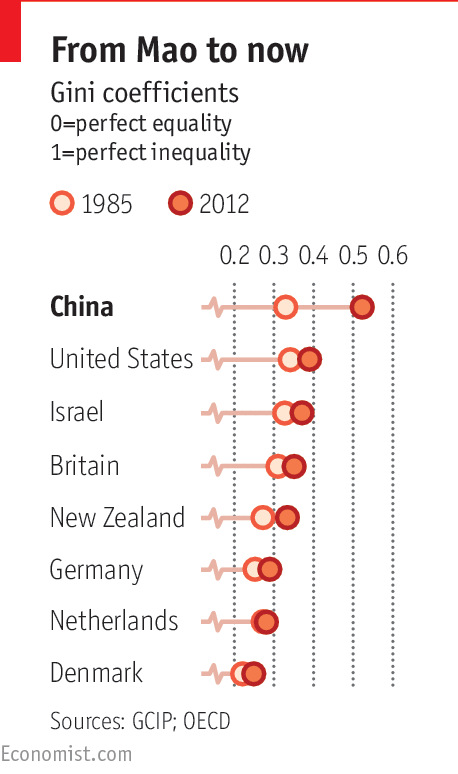

Most of China’s middle classes own property and have decent jobs, yet they, too, worry that they are being squeezed, both from the bottom and the top. In the 1980s China was among the most equal societies in the world, with a Gini coefficient of 0.3 (the Gini is a standard measure of income inequality in which 0 means total equality and 1 total inequality). By 2008 it had risen to a peak of 0.49. For the past seven years it has been declining slightly as pay for rural and blue-collar jobs has been rising faster than for white-collar ones, but at 0.46 the official figure is still higher than anywhere in the OECD, a club of mainly rich countries (see chart), and many unofficial estimates are higher.

Despite that narrowing of the income gap, in other respects people feel that inequality is getting worse. That is partly because of the way they think about success. Traditionally they compared their lives with those of their parents, which should leave almost everyone feeling better off. But today’s young tend to think horizontally, says Jean Wei-Jun Yeung of the National University of Singapore, and judge themselves against their peers. City folk are far more likely to run into the full spectrum of inequality in their own streets, and thanks to the internet and television they are also well aware of how their global counterparts are doing. That helps explain why a report on well-being in China by researchers from Oxford University in Britain and Monash University in Australia, published last year, found that a rise in rural incomes has a far more positive effect on happiness than in urban ones.

The middle class’s biggest grievance is that the super-rich have surged ahead and appear to have pulled up the ladder behind them. Beijing now has more billionaires than New York, according to Hurun, a Shanghai luxury publishing company. It calculates that the combined net worth of the country’s 568 billionaires is much the same as Australia’s total GDP. A study by Peking University earlier this year found that the top 1% of Chinese households controlled a third of the country’s assets, many of them in the form of “hidden income”, or undeclared earnings. Wang Xiaolu of the National Economic Research Institute in Beijing reckons that if hidden income is included, the top 10% earned 21 times as much as the bottom 10% in 2011, compared with official estimates of nine times. The distance between the upper and lower ends of the middle class is growing too, according to Boston Consulting Group, a consultancy.

Many middle-class folk feel that, having fought their way up, they are being rewarded ever less generously for their efforts. Returns to education are declining because universities have expanded rapidly. Last year more than 7m students completed university degrees, compared with fewer than 1m in 2000. That makes society more equal, but middle-class households fret that new graduates are finding it harder to get good jobs.

The squeezed middle

The party has helped hundreds of millions of people get richer, but has done little to ensure that their assets serve them well

Many think the gap between the super-wealthy and the rest is growing because the game is rigged. They see society as unfair, divided between those with connections and those without. A lot of Chinese believe, often correctly, that having personal networks which include powerful people trumps hard work. State-owned enterprises account for only one-third of GDP, but they control key sectors such as energy and finance that affect every company, big or small. Even if no graft is involved, people “who know people” find out about new policies and projects first, says Kong Miao, aged 25, who runs a startup in Beijing: “It’s not a problem of corruption, it’s a problem of information asymmetry.” As long as the government maintains a monopoly on the commanding heights of the economy, this will remain true.

The party is well aware that inequality is bad for social stability. From 1978 onwards it consistently said that its “chief task” was economic construction, but in 2006 it changed its goal to establishing a “harmonious society” by 2020. It seems reasonable to help the poorest in society move up, but that could make the middling sort feel even more unsettled.

Of all the social groups in China, the middle classes seem to have the most to lose from instability. Most are primarily interested in making money, but some now worry that their precious assets are in jeopardy. The party has helped hundreds of millions of people get richer, but has done little to ensure that their assets serve them well. Pension and insurance schemes are weak. The super-rich often park money abroad, but the merely well off find that harder to do. And the choices on offer at home look less than enticing. It may prove a fatal flaw—not only for the economy, but for confidence in the underlying political system—that the party failed to build a proper legal system at the same time as it launched a roaring economy.

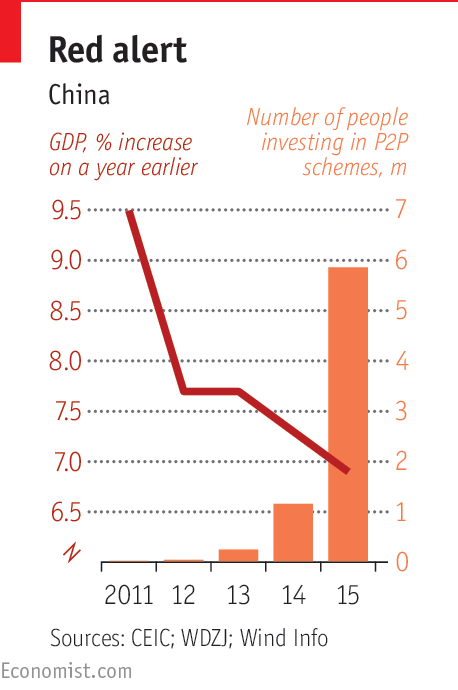

Banks in China frequently offer interest rates below the level of inflation, so people look elsewhere to protect their savings. Around 15% of household financial assets are invested in the stockmarket, not enough to sink the economy when the market plunged last year but plenty to anger large numbers of stockholders. Around 3m people have also invested in peer-to-peer schemes, which have proliferated in recent years. That so many individuals and small businesses are prepared to put their money into products they know little about is a “manifestation of people’s deep desperation in a slowing economy”, says Edward Cunningham of Harvard University. And some of them have been badly burned.

In 2014 Ding Ning, an entrepreneur who had made a fortune manufacturing screws and tin-openers, started a company called Ezubao. It quickly became China’s largest peer-to-peer lender, attracting 50 billion yuan ($7.6 billion) from nearly 1m investors. It advertised returns of 9-15%, many times what traditional banks could offer. A government body even named it a “Model Enterprise” for e-commerce integrity. Unfortunately it turned out to be the wrong kind of model. Last year the government froze its assets; in February it pronounced the company a Ponzi scheme, the world’s largest by number of depositors. Almost all the money that flowed out to long-term investors came from deposits by new ones.

When Ezubao collapsed, protesters gathered in several cities, and hundreds of social-media groups formed online to discuss “rights protection”—just the kind of widely dispersed protest the state fears. Depositors were angry not only because they had lost money, but because they felt it had been “deliberate government policy” to encourage investment in such products, says Victor Shih of the University of California, San Diego. The case of Ezubao is unusual—and significant—because the protests were directed at the central government rather than the local authorities or institutions that typically attract such criticism. According to Harvard’s Mr Cunningham, amateur investors in Ezubao believed that the central government had endorsed the scheme, and were furious when they found their trust had been misplaced. “It’s like giving a car to someone who doesn’t have a driver’s licence and letting him rampage around recklessly,” says a 32-year-old investor from Ningbo, near Shanghai, who had put 150,000 yuan into Ezubao after seeing ads in state media and read endorsements from state-owned companies. “The government is irresponsible, I’m truly disappointed in this country.”

The party has no good explanation. Either it knew about the Ponzi scheme and did not warn investors, or it was oblivious to the scam when it should have known about it. At the very least, it failed to provide adequate regulation: more than a third of the 4,000 peer-to-peer platforms launched in recent years have failed. And since China has no independent judiciary, it lacks any system of trustworthy dispute resolution.

Things are getting worse. Between 2003 and 2013, courts across China ruled on 1,051 cases of financial fraud and “illegal poolings” of public savings, including Ponzi schemes. Last year there were nearly 4,000 cases, and in the first three months of 2016 alone a further 2,300 were uncovered. In the past year financial frauds have cost investors at least $20 billion. Although the government has belatedly woken up to the problem, so far its main response has been to ban the registration of new companies with the word “finance” in their title. Peer-to-peer schemes still account for only a tiny share of household savings, but their failure shows how hard it is to ensure that savings are safe.

From homes to castles

Since there are so few outlets in China for investing profitably and safely, putting savings into property is even more popular than elsewhere. Urban housing was privatised only in the 1990s, but already around 85% of city folk own their homes. Yet property rights are shaky. Time after time, apartment-owners have formed residents’ associations to fight plans to build additional towers close to theirs, usually in vain. In some cases buyers have shelled out for apartments before they were built, only for the developers to disappear with the funds.

A recent series of cases in Zhejiang province revealed the weakness of China’s legal framework for property rights. Since the party abolished land and property ownership after 1949 there have been no freeholds in China, and leases are typically 70 years for urban residential properties, but some are much shorter. Earlier this year hundreds of people who had signed 20-year leases on property in the wealthy city of Wenzhou in the 1990s were asked to pay a third of their homes’ market value to renew the leases. This provoked an outcry on social media, and Xinhua, the state news agency, warned that a blurry definition of home ownership could cause unrest. The 20-year leases on thousands of other apartments in Wenzhou and other coastal cities are due to expire in 2019.

Not in my courtyard

Property owners were dealt another blow in February with China-wide proposals to stop the building of new gated communities and gradually open up the many parts of Chinese cities that have been shut away behind fences and gates since the 1990s. The idea was to relieve pressure on the overcrowded road network and make better use of urban land, but it proved inflammatory. Within 12 hours the news had been forwarded tens of thousands of times on social media. Many complained that the proposal contravened a 2007 property law under which roads within such zones belong to the homeowners. The indignation was not just about money. Owning a residence in a gated community is seen as a sign of upward mobility, a domestic space removed from state control. It is the opposite to the Mao-era danwei or work unit, where the state told everyone where to live and neighbours all knew and monitored each other. Millions of people now question whether their assets are safe from some as yet unsuspected new plan. Even though the Chinese have little appetite for political change, they have a huge thirst for security, transparency and the rule of law.

The cost of housing is soaring in China’s biggest and most desirable cities. In Shanghai, for example, it rose by 20% over the past year. That is good for those who already own a property, but frustrating for young people hoping to buy in the next few years before getting married. It also raises fears that the next generation will fare less well than the current one, especially in view of slowing growth. And as middle-class certainties are being called into question, people are becoming more vocal. |