Source: theamericanconservative.comThe New Legalist editor's note: Though this long eassay was posted nearly 3 years ago, it seems unlikely that the situation has much changed, still less changed for the better.

Just before the Labor Day weekend, a front page New York Times story broke the news of the largest cheating scandal in Harvard University history, in which nearly half the students taking a Government course on the role of Congress had plagiarized or otherwise illegally collaborated on their final exam.1 Each year, Harvard admits just 1600 freshmen while almost 125 Harvard students now face possible suspension over this single incident. A Harvard dean described the situation as “unprecedented.”

But should we really be so surprised at this behavior among the students at America’s most prestigious academic institution? In the last generation or two, the funnel of opportunity in American society has drastically narrowed, with a greater and greater proportion of our financial, media, business, and political elites being drawn from a relatively small number of our leading universities, together with their professional schools. The rise of a Henry Ford, from farm boy mechanic to world business tycoon, seems virtually impossible today, as even America’s most successful college dropouts such as Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg often turn out to be extremely well-connected former Harvard students. Indeed, the early success of Facebook was largely due to the powerful imprimatur it enjoyed from its exclusive availability first only at Harvard and later restricted to just the Ivy League.

During this period, we have witnessed a huge national decline in well-paid middle class jobs in the manufacturing sector and other sources of employment for those lacking college degrees, with median American wages having been stagnant or declining for the last forty years. Meanwhile, there has been an astonishing concentration of wealth at the top, with America’s richest 1 percent now possessing nearly as much net wealth as the bottom 95 percent.2 This situation, sometimes described as a “winner take all society,” leaves families desperate to maximize the chances that their children will reach the winners’ circle, rather than risk failure and poverty or even merely a spot in the rapidly deteriorating middle class. And the best single means of becoming such an economic winner is to gain admission to a top university, which provides an easy ticket to the wealth of Wall Street or similar venues, whose leading firms increasingly restrict their hiring to graduates of the Ivy League or a tiny handful of other top colleges.3 On the other side, finance remains the favored employment choice for Harvard, Yale or Princeton students after the diplomas are handed out.4 During this period, we have witnessed a huge national decline in well-paid middle class jobs in the manufacturing sector and other sources of employment for those lacking college degrees, with median American wages having been stagnant or declining for the last forty years. Meanwhile, there has been an astonishing concentration of wealth at the top, with America’s richest 1 percent now possessing nearly as much net wealth as the bottom 95 percent.2 This situation, sometimes described as a “winner take all society,” leaves families desperate to maximize the chances that their children will reach the winners’ circle, rather than risk failure and poverty or even merely a spot in the rapidly deteriorating middle class. And the best single means of becoming such an economic winner is to gain admission to a top university, which provides an easy ticket to the wealth of Wall Street or similar venues, whose leading firms increasingly restrict their hiring to graduates of the Ivy League or a tiny handful of other top colleges.3 On the other side, finance remains the favored employment choice for Harvard, Yale or Princeton students after the diplomas are handed out.4

The Battle for Elite College Admissions

As a direct consequence, the war over college admissions has become astonishingly fierce, with many middle- or upper-middle class families investing quantities of time and money that would have seemed unimaginable a generation or more ago, leading to an all-against-all arms race that immiserates the student and exhausts the parents. The absurd parental efforts of an Amy Chua, as recounted in her 2010 bestseller Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, were simply a much more extreme version of widespread behavior among her peer-group, which is why her story resonated so deeply among our educated elites. Over the last thirty years, America’s test-prep companies have grown from almost nothing into a $5 billion annual industry, allowing the affluent to provide an admissions edge to their less able children. Similarly, the enormous annual tuition of $35,000 charged by elite private schools such as Dalton or Exeter is less for a superior high school education than for the hope of a greatly increased chance to enter the Ivy League.5 Many New York City parents even go to enormous efforts to enroll their children in the best possible pre-Kindergarten program, seeking early placement on the educational conveyer belt which eventually leads to Harvard.6 Others cut corners in a more direct fashion, as revealed in the huge SAT cheating rings recently uncovered in affluent New York suburbs, in which students were paid thousands of dollars to take SAT exams for their wealthier but dimmer classmates.7

But given such massive social and economic value now concentrated in a Harvard or Yale degree, the tiny handful of elite admissions gatekeepers enjoy enormous, almost unprecedented power to shape the leadership of our society by allocating their supply of thick envelopes. Even billionaires, media barons, and U.S. Senators may weigh their words and actions more carefully as their children approach college age. And if such power is used to select our future elites in a corrupt manner, perhaps the inevitable result is the selection of corrupt elites, with terrible consequences for America. Thus, the huge Harvard cheating scandal, and perhaps also the endless series of financial, business, and political scandals which have rocked our country over the last decade or more, even while our national economy has stagnated.

Just a few years ago Pulitzer Prize-winning former Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Golden published The Price of Admission, a devastating account of the corrupt admissions practices at so many of our leading universities, in which every sort of non-academic or financial factor plays a role in privileging the privileged and thereby squeezing out those high-ability, hard-working students who lack any special hook. In one particularly egregious case, a wealthy New Jersey real estate developer, later sent to Federal prison on political corruption charges, paid Harvard $2.5 million to help ensure admission of his completely under-qualified son.8 When we consider that Harvard’s existing endowment was then at $15 billion and earning almost $7 million each day in investment earnings, we see that a culture of financial corruption has developed an absurd illogic of its own, in which senior Harvard administrators sell their university’s honor for just a few hours worth of its regular annual income, the equivalent of a Harvard instructor raising a grade for a hundred dollars in cash.

An admissions system based on non-academic factors often amounting to institutionalized venality would seem strange or even unthinkable among the top universities of most other advanced nations in Europe or Asia, though such practices are widespread in much of the corrupt Third World. The notion of a wealthy family buying their son his entrance into the Grandes Ecoles of France or the top Japanese universities would be an absurdity, and the academic rectitude of Europe’s Nordic or Germanic nations is even more severe, with those far more egalitarian societies anyway tending to deemphasize university rankings.

Or consider the case of China. There, legions of angry microbloggers endlessly denounce the official corruption and abuse which permeate so much of the economic system. But we almost never hear accusations of favoritism in university admissions, and this impression of strict meritocracy determined by the results of the national Gaokao college entrance examination has been confirmed to me by individuals familiar with that country. Since all the world’s written exams may ultimately derive from China’s old imperial examination system, which was kept remarkably clean for 1300 years, such practices are hardly surprising.9 Attending a prestigious college is regarded by ordinary Chinese as their children’s greatest hope of rapid upward mobility and is therefore often a focus of enormous family effort; China’s ruling elites may rightly fear that a policy of admitting their own dim and lazy heirs to leading schools ahead of the higher-scoring children of the masses might ignite a widespread popular uprising. This perhaps explains why so many sons and daughters of top Chinese leaders attend college in the West: enrolling them at a third-rate Chinese university would be a tremendous humiliation, while our own corrupt admissions practices get them an easy spot at Harvard or Stanford, sitting side by side with the children of Bill Clinton, Al Gore, and George W. Bush.

Although the evidence of college admissions corruption presented in Golden’s book is quite telling, the focus is almost entirely on current practices, and largely anecdotal rather than statistical. For a broader historical perspective, we should consider The Chosen by Berkeley sociologist Jerome Karabel, an exhaustive and award-winning 2005 narrative history of the last century of admissions policy at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton (I will henceforth sometimes abbreviate these “top three” most elite schools as “HYP”).

Karabel’s massive documentation—over 700 pages and 3000 endnotes—establishes the remarkable fact that America’s uniquely complex and subjective system of academic admissions actually arose as a means of covert ethnic tribal warfare. During the 1920s, the established Northeastern Anglo-Saxon elites who then dominated the Ivy League wished to sharply curtail the rapidly growing numbers of Jewish students, but their initial attempts to impose simple numerical quotas provoked enormous controversy and faculty opposition.10 Therefore, the approach subsequently taken by Harvard President A. Lawrence Lowell and his peers was to transform the admissions process from a simple objective test of academic merit into a complex and holistic consideration of all aspects of each individual applicant; the resulting opacity permitted the admission or rejection of any given applicant, allowing the ethnicity of the student body to be shaped as desired. As a consequence, university leaders could honestly deny the existence of any racial or religious quotas, while still managing to reduce Jewish enrollment to a much lower level, and thereafter hold it almost constant during the decades which followed.11 For example, the Jewish portion of Harvard’s entering class dropped from nearly 30 percent in 1925 to 15 percent the following year and remained roughly static until the period of the Second World War.12

As Karabel repeatedly demonstrates, the major changes in admissions policy which later followed were usually determined by factors of raw political power and the balance of contending forces rather than any idealistic considerations. For example, in the aftermath of World War II, Jewish organizations and their allies mobilized their political and media resources to pressure the universities into increasing their ethnic enrollment by modifying the weight assigned to various academic and non-academic factors, raising the importance of the former over the latter. Then a decade or two later, this exact process was repeated in the opposite direction, as the early 1960s saw black activists and their liberal political allies pressure universities to bring their racial minority enrollments into closer alignment with America’s national population by partially shifting away from their recently enshrined focus on purely academic considerations. Indeed, Karabel notes that the most sudden and extreme increase in minority enrollment took place at Yale in the years 1968–69, and was largely due to fears of race riots in heavily black New Haven, which surrounded the campus.13

Philosophical consistency appears notably absent in many of the prominent figures involved in these admissions battles, with both liberals and conservatives sometimes favoring academic merit and sometimes non-academic factors, whichever would produce the particular ethnic student mix they desired for personal or ideological reasons. Different political blocs waged long battles for control of particular universities, and sudden large shifts in admissions rates occurred as these groups gained or lost influence within the university apparatus: Yale replaced its admissions staff in 1965 and the following year Jewish numbers nearly doubled.14

At times, external judicial or political forces would be summoned to override university admissions policy, often succeeding in this aim. Karabel’s own ideological leanings are hardly invisible, as he hails efforts by state legislatures to force Ivy League schools to lift their de facto Jewish quotas, but seems to regard later legislative attacks on “affirmative action” as unreasonable assaults on academic freedom.15 The massively footnoted text of The Chosen might lead one to paraphrase Clausewitz and conclude that our elite college admissions policy often consists of ethnic warfare waged by other means, or even that it could be summarized as a simple Leninesque question of “Who, Whom?”

Although nearly all of Karabel’s study is focused on the earlier history of admissions policy at Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, with the developments of the last three decades being covered in just a few dozen pages, he finds complete continuity down to the present day, with the notorious opacity of the admissions process still allowing most private universities to admit whomever they want for whatever reasons they want, even if the reasons and the admissions decisions may eventually change over the years. Despite these plain facts, Harvard and the other top Ivy League schools today publicly deny any hint of discrimination along racial or ethnic lines, except insofar as they acknowledge providing an admissions boost to under-represented racial minorities, such as blacks or Hispanics. But given the enormous control these institutions exert on our larger society, we should test these claims against the evidence of the actual enrollment statistics.

Asian-Americans as the “New Jews”

The overwhelming focus of Karabel’s book is on changes in Jewish undergraduate percentages at each university, and this is probably less due to his own ethnic heritage than because the data provides an extremely simple means of charting the ebb and flow of admissions policy: Jews were a high-performing group, whose numbers could only be restricted by major deviations from an objective meritocratic standard.

Obviously, anti-Jewish discrimination in admissions no longer exists at any of these institutions, but a roughly analogous situation may be found with a group whom Golden and others have sometimes labeled “The New Jews,” namely Asian-Americans. Since their strong academic performance is coupled with relatively little political power, they would be obvious candidates for discrimination in the harsh realpolitik of university admissions as documented by Karabel, and indeed he briefly raises the possibility of an anti-Asian admissions bias, before concluding that the elite universities are apparently correct in denying that it exists.16

There certainly does seem considerable anecdotal evidence that many Asians perceive their chances of elite admission as being drastically reduced by their racial origins.17 For example, our national newspapers have revealed that students of part-Asian background have regularly attempted to conceal the non-white side of their ancestry when applying to Harvard and other elite universities out of concern it would greatly reduce their chances of admission.18 Indeed, widespread perceptions of racial discrimination are almost certainly the primary factor behind the huge growth in the number of students refusing to reveal their racial background at top universities, with the percentage of Harvard students classified as “race unknown” having risen from almost nothing to a regular 5–15 percent of all undergraduates over the last twenty years, with similar levels reached at other elite schools.

Such fears that checking the “Asian” box on an admissions application may lead to rejection are hardly unreasonable, given that studies have documented a large gap between the average test scores of whites and Asians successfully admitted to elite universities. Princeton sociologist Thomas J. Espenshade and his colleagues have demonstrated that among undergraduates at highly selective schools such as the Ivy League, white students have mean scores 310 points higher on the 1600 SAT scale than their black classmates, but Asian students average 140 points above whites.19 The former gap is an automatic consequence of officially acknowledged affirmative action policies, while the latter appears somewhat mysterious.

These broad statistical differences in the admission requirements for Asians are given a human face in Golden’s discussions of this subject, in which he recounts numerous examples of Asian-American students who overcame dire family poverty, immigrant adversity, and other enormous personal hardships to achieve stellar academic performance and extracurricular triumphs, only to be rejected by all their top university choices. His chapter is actually entitled “The New Jews,” and he notes the considerable irony that a university such as Vanderbilt will announce a public goal of greatly increasing its Jewish enrollment and nearly triple those numbers in just four years, while showing very little interest in admitting high-performing Asian students.20

All these elite universities strongly deny the existence of any sort of racial discrimination against Asians in the admissions process, let alone an “Asian quota,” with senior administrators instead claiming that the potential of each student is individually evaluated via a holistic process far superior to any mechanical reliance on grades or test scores; but such public postures are identical to those taken by their academic predecessors in the 1920s and 1930s as documented by Karabel. Fortunately, we can investigate the plausibility of these claims by examining the decades of officially reported enrollment data available from the website of the National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES).

The ethnic composition of Harvard undergraduates certainly follows a highly intriguing pattern. Harvard had always had a significant Asian-American enrollment, generally running around 5 percent when I had attended in the early 1980s. But during the following decade, the size of America’s Asian middle class grew rapidly, leading to a sharp rise in applications and admissions, with Asians exceeding 10 percent of undergraduates by the late 1980s and crossing the 20 percent threshold by 1993. However, from that year forward, the Asian numbers went into reverse, generally stagnating or declining during the two decades which followed, with the official 2011 figure being 17.2 percent.21

Even more surprising has been the sheer constancy of these percentages, with almost every year from 1995–2011 showing an Asian enrollment within a single point of the 16.5 percent average, despite huge fluctuations in the number of applications and the inevitable uncertainty surrounding which students will accept admission. By contrast, prior to 1993 Asian enrollment had often changed quite substantially from year to year. It is interesting to note that this exactly replicates the historical pattern observed by Karabel, in which Jewish enrollment rose very rapidly, leading to imposition of an informal quota system, after which the number of Jews fell substantially, and thereafter remained roughly constant for decades. On the face of it, ethnic enrollment levels which widely diverge from academic performance data or application rates and which remain remarkably static over time provide obvious circumstantial evidence for at least a de facto ethnic quota system.

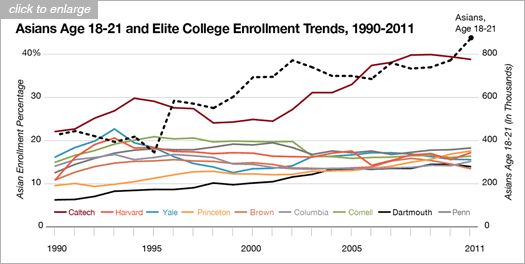

In another strong historical parallel, all the other Ivy League universities seem to have gone through similar shifts in Asian enrollment at similar times and reached a similar plateau over the last couple of decades. As mentioned, the share of Asians at Harvard peaked at over 20 percent in 1993, then immediately declined and thereafter remained roughly constant at a level 3–5 points lower. Asians at Yale reached a 16.8 percent maximum in that same year, and soon dropped by about 3 points to a roughly constant level. The Columbia peak also came in 1993 and the Cornell peak in 1995, in both cases followed by the same substantial drop, and the same is true for most of their East Coast peers. During the mid- to late-1980s, there had been some public controversy in the media regarding allegations of anti-Asian discrimination in the Ivy League, and the Federal Government eventually even opened an investigation into the matter.22 But once that investigation was closed in 1991, Asian enrollments across all those universities rapidly converged to the same level of approximately 16 percent, and remained roughly static thereafter (See chart below). In fact, the yearly fluctuations in Asian enrollments are often smaller than were the changes in Jewish numbers during the “quota era” of the past,23 and are roughly the same relative size as the fluctuations in black enrollments, even though the latter are heavily influenced by the publicly declared “ethnic diversity goals” of those same institutions.

The largely constant Asian numbers at these elite colleges are particularly strange when we consider that the underlying population of Asians in America has been anything but static, instead growing at the fastest pace of any American racial group, having increased by almost 50 percent during the last decade, and more than doubling since 1993. Obviously, the relevant ratio would be to the 18–21 age cohort, but adjusting for this factor changes little: based on Census data, the college-age ratio of Asians to whites increased by 94 percent between 1994 and 2011, even while the ratio of Asians to whites at Harvard and Columbia fell over these same years.24

Put another way, the percentage of college-age Asian-Americans attending Harvard peaked around 1993, and has since dropped by over 50 percent, a decline somewhat larger than the fall in Jewish enrollment which followed the imposition of secret quotas in 1925.25 And we have noted the parallel trends in the other Ivy League schools, which also replicates the historical pattern.

Trends of Asian enrollment at Caltech and the Ivy League universities, compared with growth of Asian college-age population; Asian age cohort population figures are based on Census CPS, and given the small sample size, are subject to considerable yearly statistical fluctuations. Source: Appendices B and C.

Furthermore, during this exact same period a large portion of the Asian-American population moved from first-generation immigrant poverty into the ranks of the middle class, greatly raising their educational aspirations for their children. Although elite universities generally refuse to release their applicant totals for different racial groups, some data occasionally becomes available. Princeton’s records show that between 1980 and 1989, Asian-American applications increased by over 400 percent compared to just 8 percent for other groups, with an even more rapid increase for Brown during 1980-1987, while Harvard’s Asian applicants increased over 250 percent between 1976 and 1985.26 It seems likely that the statistics for other Ivy League schools would have followed a similar pattern and these trends would have at least partially continued over the decades which followed, just as the Asian presence has skyrocketed at selective public feeder schools such as Stuyvesant and Bronx Science in New York City and also at the top East Coast prep schools. Yet none of these huge changes in the underlying pool of Asian applicants seemed to have had noticeable impact on the number admitted to Harvard or most of the Ivy League.

Estimating Asian Merit

One obvious possible explanation for these trends might be a decline in average Asian scholastic performance, which would certainly be possible if more and more Asian students from the lower levels of the ability pool were pursuing an elite education.27 The mean SAT scores for Asian students show no such large decline, but since we would expect elite universities to draw their students from near the absolute top of the performance curve, average scores by race are potentially less significant than the Asian fraction of America’s highest performing students.

To the extent that the hundred thousand or so undergraduates at Ivy League schools and their approximate peers are selected by academic merit, they would mostly be drawn from the top one-half to one percent of their American age-cohort, and this is the appropriate pool to consider. It is perfectly possible that a particular ethnic population might have a relatively high mean SAT score, while still being somewhat less well represented in that top percent or so of measured ability; racial performance does not necessarily follow an exact “bell curve” distribution. For one thing, a Census category such as “Asian” is hardly homogenous or monolithic, with South Asians and East Asians such as Chinese and Koreans generally having much higher performance compared to other groups such as Filipinos, Vietnamese, or Cambodians, just as the various types of “Hispanics” such as Cubans, Mexicans, and Puerto Ricans differ widely in their socio-economic and academic profiles. Furthermore, the percentage of a given group taking the SAT may change over time, and the larger the percentage taking that test, the more that total will include weaker students, thereby depressing the average score.

Fortunately, allegations of anti-Asian admissions bias have become a topic of widespread and heated debate on the Internet, and disgruntled Asian-American activists have diligently located various types of data to support their accusations, with the recent ethnic distribution of National Merit Scholarship (NMS) semifinalists being among the most persuasive. Students receiving this official designation represent approximately the top one-half of one percent of a state’s high school students as determined by their scores on the PSAT, twin brother to the SAT. Each year, the NMS Corporation distributes the names and schools of these semifinalists for each state, and dozens of these listings have been tracked down and linked on the Internet by determined activists, who have then sometimes estimated the ethnic distribution of the semifinalists by examining their family names.28 Obviously, such a name analysis provides merely an approximate result, but the figures are striking enough to warrant the exercise. (All these NMS semifinalist estimates are discussed in Appendix E.)29

For example, California has a population comparable to that of the next two largest states combined, and its 2010 total of 2,003 NMS semifinalists included well over 1,100 East Asian or South Asian family names. California may be one of the most heavily Asian states, but even so Asians of high school age are still outnumbered by whites roughly 3-to-1, while there were far more high scoring Asians. Put another way, although Asians represented only about 11 percent of California high school students, they constituted almost 60 percent of the top scoring ones. California’s list of NMS semifinalists from 2012 also followed a very similar ethnic pattern. Obviously, such an analysis based on last names is hardly precise, but it is probably correct to within a few percent, which is sufficient for our crude analytical purposes.

In addition, the number of test-takers is sufficiently large that an examination of especially distinctive last names allows us to pinpoint and roughly quantify the academic performance of different Asian groups. For example, the name “Nguyen” is uniquely Vietnamese and carried by about 1 in 3.6 of all Americans of that ethnicity, while “Kim” is just as uniquely Korean, with one in 5.5 Korean-Americans bearing that name.30 By comparing the prevalence of these particular names on the California NMS semifinalist lists with the total size of the corresponding California ethnicities, we can estimate that California Vietnamese are significantly more likely than whites to score very highly on such tests, while Koreans seem to do eight times better than whites and California’s Chinese even better still. (All these results rely upon the simplifying assumption that these different Asian groups are roughly proportional in their numbers of high school seniors.)

Interestingly enough, these Asian performance ratios are remarkably similar to those worked out by Nathaniel Weyl in his 1989 book The Geography of American Achievement, in which he estimated that Korean and Chinese names were over-represented by 1000 percent or more on the complete 1987 lists of national NMS semifinalists, while Vietnamese names were only somewhat more likely to appear than the white average.31 This consistency is quite impressive when we consider that America’s Asian population has tripled since the late 1980s, with major changes as well in socio-economic distribution and other characteristics.

The results for states other than California reflect this same huge abundance of high performing Asian students. In Texas, Asians are just 3.8 percent of the population but were over a quarter of the NMS semifinalists in 2010, while the 2.4 percent of Florida Asians provided between 10 percent and 16 percent of the top students in the six years from 2008 to 2013 for which I have been able to obtain the NMS lists. Even in New York, which contains one of our nation’s most affluent and highly educated white populations and also remains by far the most heavily Jewish state, Asian over-representation was enormous: the Asian 7.3 percent of the population—many of them impoverished immigrant families—accounted for almost one-third of all top scoring New York students.

America’s eight largest states contain nearly half our total population as well as over 60 percent of all Asian-Americans, and each has at least one NMS semifinalist list available for the years 2010–2012. Asians account for just 6 percent of the population in these states, but contribute almost one-third of all the names on these rosters of high performing students. Even this result may be a substantial underestimate, since over half these Asians are found in gigantic California, where extremely stiff academic competition has driven the qualifying NMS semifinalist threshold score to nearly the highest in the country; if students were selected based on a single nationwide standard, Asian numbers would surely be much higher. This pattern extends to the aggregate of the twenty-five states whose lists are available, with Asians constituting 5 percent of the total population but almost 28 percent of semifinalists. Extrapolating these state results to the national total, we would expect 25–30 percent of America’s highest scoring high school seniors to be of Asian origin.32 This figure is far above the current Asian enrollment at Harvard or the rest of the Ivy League.

Ironically enough, the methodology used to select these NMS semifinalists may considerably understate the actual number of very high-ability Asian students. According to testing experts, the three main subcomponents of intellectual ability are verbal, mathematical, and visuospatial, with the last of these representing the mental manipulation of objects. Yet the qualifying NMS scores are based on math, reading, and writing tests, with the last two both corresponding to verbal ability, and without any test of visuospatial skills. Even leaving aside the language difficulties which students from an immigrant background might face, East Asians tend to be weakest in the verbal category and strongest in the visuospatial, so NMS semifinalists are being selected by a process which excludes the strongest Asian component and doubles the weight of the weakest.33

This evidence of a massively disproportionate Asian presence among top-performing students only increases if we examine the winners of national academic competitions, especially those in mathematics and science, where judging is the most objective. Each year, America picks its five strongest students to represent our country in the International Math Olympiad, and during the three decades since 1980, some 34 percent of these team members have been Asian-American, with the corresponding figure for the International Computing Olympiad being 27 percent. The Intel Science Talent Search, begun in 1942 under the auspices of the Westinghouse Corporation, is America’s most prestigious high school science competition, and since 1980 some 32 percent of the 1320 finalists have been of Asian ancestry (see Appendix F).

Given that Asians accounted for just 1.5 percent of the population in 1980 and often lived in relatively impoverished immigrant families, the longer-term historical trends are even more striking. Asians were less than 10 percent of U.S. Math Olympiad winners during the 1980s, but rose to a striking 58 percent of the total during the last thirteen years 2000–2012. For the Computing Olympiad, Asian winners averaged about 20 percent of the total during most of the 1990s and 2000s, but grew to 50 percent during 2009–2010 and a remarkable 75 percent during 2011–2012.

The statistical trend for the Science Talent Search finalists, numbering many thousands of top science students, has been the clearest: Asians constituted 22 percent of the total in the 1980s, 29 percent in the 1990s, 36 percent in the 2000s, and 64 percent in the 2010s. In particular science subjects, the Physics Olympiad winners follow a similar trajectory, with Asians accounting for 23 percent of the winners during the 1980s, 25 percent during the 1990s, 46 percent during the 2000s, and a remarkable 81 percent since 2010. The 2003–2012 Biology Olympiad winners were 68 percent Asian and Asians took an astonishing 90 percent of the top spots in the recent Chemistry Olympiads. Some 61 percent of the Siemens AP Awards from 2002–2011 went to Asians, including thirteen of the fourteen top national prizes.

Yet even while all these specific Asian-American academic achievement trends were rising at such an impressive pace, the relative enrollment of Asians at Harvard was plummeting, dropping by over half during the last twenty years, with a range of similar declines also occurring at Yale, Cornell, and most other Ivy League universities. Columbia, in the heart of heavily Asian New York City, showed the steepest decline of all.

There may even be a logical connection between these two contradictory trends. On the one hand, America over the last two decades has produced a rapidly increasing population of college-age Asians, whose families are increasingly affluent, well-educated, and eager to secure an elite education for their children. But on the other hand, it appears that these leading academic institutions have placed a rather strict upper limit on actual Asian enrollments, forcing these Asian students to compete more and more fiercely for a very restricted number of openings. This has sparked a massive Asian-American arms-race in academic performance at high schools throughout the country, as seen above in the skyrocketing math and science competition results. When a far greater volume of applicants is squeezed into a pipeline of fixed size, the pressure can grow enormously.

The implications of such massive pressure may be seen in a widely-discussed front page 2005 Wall Street Journal story entitled “The New White Flight.”34 The article described the extreme academic intensity at several predominantly Asian high schools in Cupertino and other towns in Silicon Valley, and the resulting exodus of white students, who preferred to avoid such an exceptionally focused and competitive academic environment, which included such severe educational tension. But should the families of those Asian students be blamed if according to Espensade and his colleagues their children require far higher academic performance than their white classmates to have a similar chance of gaining admission to selective colleges?

Although the “Asian Tiger Mom” behavior described by author Amy Chua provoked widespread hostility and ridicule, consider the situation from her perspective. Being herself a Harvard graduate, she would like her daughters to follow in her own Ivy League footsteps, but is probably aware that the vast growth in Asian applicants with no corresponding increase in allocated Asian slots requires heroic efforts to shape the perfect application package. Since Chua’s husband is not Asian, she could obviously encourage her children to improve their admissions chances by concealing their ethnic identity during the application process; but this would surely represent an enormous personal humiliation for a proud and highly successful Illinois-born American of Chinese ancestry.

The claim that most elite American universities employ a de facto Asian quota system is certainly an inflammatory charge in our society. Indeed, our media and cultural elites view any accusations of “racial discrimination” as being among the most horrific of all possible charges, sometimes even regarded as more serious than mass murder.35 So before concluding that these accusations are probably true and considering possible social remedies, we should carefully reconsider their plausibility, given that they are largely based upon a mixture of circumstantial statistical evidence and the individual anecdotal cases presented by Golden and a small handful of other critical journalists. One obvious approach is to examine enrollment figures at those universities which for one reason or another may follow a different policy.

According to incoming student test scores and recent percentages of National Merit Scholars, four American universities stand at the absolute summit of average student quality—Harvard, Yale, Princeton, and Caltech, the California Institute of Technology; and of these Caltech probably ranks first among equals.36 Those three top Ivies continue to employ the same admissions system which Karabel describes as “opaque,” “flexible,” and allowing enormous “discretion,”37 a system originally established to restrict the admission of high-performing Jews. But Caltech selects its students by strict academic standards, with Golden praising it for being America’s shining example of a purely meritocratic university, almost untouched by the financial or political corruption so widespread in our other elite institutions. And since the beginning of the 1990s, Caltech’s Asian-American enrollment has risen almost exactly in line with the growth of America’s underlying Asian population, with Asians now constituting nearly 40 percent of each class (See chart on p. 18).

Obviously, the Caltech curriculum is narrowly focused on mathematics, science, and engineering, and since Asians tend to be especially strong in those subjects, the enrollment statistics might be somewhat distorted compared to a more academically balanced university. Therefore, we should also consider the enrollment figures for the highly-regarded University of California system, particularly its five most prestigious and selective campuses: Berkeley, UCLA, San Diego, Davis, and Irvine. The 1996 passage of Proposition 209 had outlawed the use of race or ethnicity in admissions decisions, and while administrative compliance has certainly not been absolute—Golden noted the evidence of some continued anti-Asian discrimination—the practices do seem to have moved in the general direction of race-blind meritocracy.38 And the 2011 Asian-American enrollment at those five elite campuses ranged from 34 percent to 49 percent, with a weighted average of almost exactly 40 percent, identical to that of Caltech.39

In considering these statistics, we must take into account that California is one of our most heavily Asian states, containing over one-quarter of the total national population, but also that a substantial fraction of UC students are drawn from other parts of the country. The recent percentage of Asian NMS semifinalists in California has ranged between 55 percent and 60 percent, while for the rest of America the figure is probably closer to 20 percent, so an overall elite-campus UC Asian-American enrollment of around 40 percent seems reasonably close to what a fully meritocratic admissions system might be expected to produce.

By contrast, consider the anomalous admissions statistics for Columbia. New York City contains America’s largest urban Asian population, and Asians are one-third or more of the entire state’s top scoring high school students. Over the last couple of decades, the local Asian population has doubled in size and Asians now constitute over two-thirds of the students attending the most selective local high schools such as Stuyvesant and Bronx Science, perhaps triple the levels during the mid-1980s.40 Yet whereas in 1993 Asians made up 22.7 percent of Columbia’s undergraduates, the total had dropped to 15.6 percent by 2011. These figures seem extremely difficult to explain except as evidence of sharp racial bias....

...... More

|