Source: marxisthumanistinitiative.org

The Failure of Capitalist Production: Underlying Causes of the Great Recession

by Andrew Kliman

Published by Pluto Press, November 2011

Paperback / 256pp. / ISBN-13: 978-0745332390

. .

“Clear, rigorous and combative. Kliman demonstrates that the current economic crisis is a consequence of the fundamental dynamic of capitalism, unlike the vast bulk of superficial contemporary commentary that passes for economic analysis.”

. – Rick Kuhn, Deutscher Prize winner, Reader in Politics at the Australian National University

“Among the myriad publications on the present day crisis, this work stands out as something unusual. Kliman cogently argues against the view that the crisis is ultimately rooted in financialization. He is an excellent theorist, and an equally excellent analyst of empirical data.”

, – Paresh Chattopadhyay, Université du Québec à Montréal

“One of the very best of the rapidly growing series of works seeking to explain our economic crisis. … The scholarship is exemplary and the writing is crystal clear. Highly recommended!”

. – Professor Bertell Ollman, New York University, author of Dance of the Dialectic

The Failure of Capitalist Production is essential reading for all Marxists and lefts interested in what caused the Great Recession. It debunks the fads and fashionable arguments of neoliberalism, underconsumption and inequality with a battery of facts. It restores Marx’s law of profitability to the centre of any explanation of capitalist crisis with compelling evidence and searching analysis. It must be read.

. – Michael Roberts, Michael Roberts Blog (full review here)

The thesis presented in the book stands out in a number of ways from many contemporary radical interpretations (notably the financialised-underconsumptionist thesis advanced by the influential Monthly Review … and that of the Marxist political geographer David Harvey). … Kliman provides far more compelling empirical evidence that American corporations’ rate of profit did not recover in a sustained manner after the early 1980s. … A crucial finding undermining the financialisation thesis is that Kliman demonstrates how American corporations have not, as is often claimed, invested a smaller share of their profit in production.

. – Socialist Voice (full review here)

“Kliman’s main argument is that the fall in the rate of profit is an indirect cause of the crisis. He argues that the economy failed to recover fully from the slumps of the 1970s and early 1980s and that this problem, and policymakers’ response to it, set the stage for the latest crisis. … This book is a major contribution to the debate on the recent economic crisis. It exposes the flaws of some of the most popular arguments on the left and reinstates the centrality of Marx’s law of profitability in explaining the crisis. This is done using plentiful empirical evidence and through a series of logical steps. Everyone who is interested in understanding the roots of the crisis must read it.”

–“After the Fall,” International Socialism, issue 134 (full review here)

More reviews and comments:

http://www.revleft.com/vb/andrew-kliman-failure-t166862/index.html?s=2e3431f2b4b083f2733fedacea7c8c6e&p=2358055

Chapters

- Introduction

- Profitability, the Credit System, and the “Destruction of Capital”

- Double, Double, Toil and Trouble: Dot-com boom and home-price bubble

- The 1970s––Not the 1980s––as Turning Point

- Falling Rates of Profit and Accumulation

- The Current-cost “Rate of Profit”

- Why the Rate of Profit Fell

- The Underconsumptionist Alternative

- What Is to Be Undone?

.

Synopsis

Chapter 1: Introduction.

Chapter 2: Sets out the theoretical framework that underlies the empirical analyses that follow. It discusses key components of Marx’s theory of crisis––the tendential fall in the rate of profit, the operation of credit markets, and the destruction of capital value through crises––and how they can help account for the latest crisis and Great Recession.

Chapter 3: Discusses the formation and bursting of the home-price bubble in the U.S., and the Panic of 2008 that resulted. It then discusses how Federal Reserve policy contributed to the formation of the bubble, arguing that the Fed wanted to prevent the United States from going the way of Japan. After Japan’s real-estate and stock-market bubbles burst at the start of the 1990s, it suffered a “lost decade,” and the Fed wanted to make sure that the bursting of the U.S. stock-market bubble of the 1990s did not have similar consequences. The latest crisis was therefore not caused only by problems in the financial and housing sectors. As far back as 2001, underlying weaknesses had brought the U.S. economy to the point where a stock-market crash could have led to long-term stagnation.

Chapter 4: Examines a variety of global and U.S. economic data and argues that they indicate that the economy never fully recovered from the recession of the 1970s. Because the slowdown in economic growth, sluggishness in the labor market, increase in borrowing relative to income, and other problems began in the 1970s or earlier, prior to the rise of neoliberalism, they are not attributable to neoliberal policies.

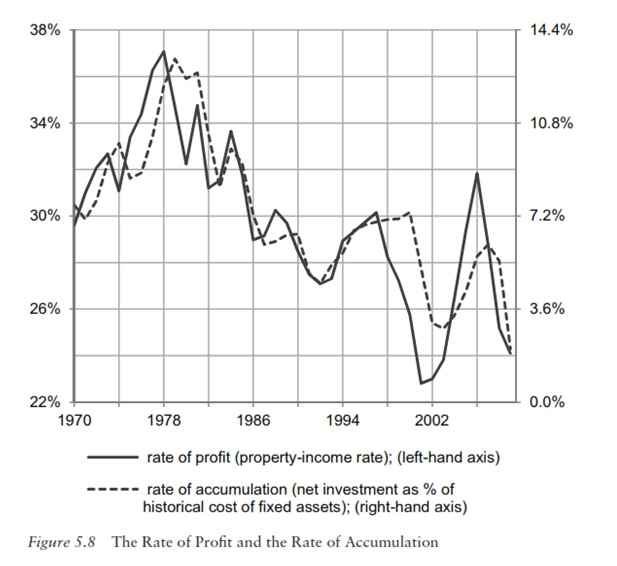

Chapter 5: Shows that U.S. corporations’ rate of profit did not rebound after the early 1980s. It also shows that the persistent fall in the rate of profit––rather than a shift from productive investment to portfolio investment––accounts for the persistent fall in the rate of accumulation.

Chapter 6: Discusses why many radical economists dismiss Marx’s law of the tendential fall in the rate of profit and contend that the rate of profit has risen. They compute “rates of profit” that value capital at its current cost (replacement cost); almost everyone else uses the term “rate of profit” to mean profit as a percentage of the actual amount of money invested in the past (net of depreciation). The current-cost “rate of profit” did indeed rebound after the early 1980s, but the author argues that it is simply not a rate of profit in any meaningful sense. In particular, although proponents of the current-cost rate have recently defended its use on the grounds that it adjusts for inflation, he argues that it mis-measures the effect of inflation and that this mis-measurement is the predominant reason why it rose.

Chapter 7: Looks at why the rate of profit fell. It shows that changes in the distribution of corporations’ output between labor and non-labor income were minor, and it decomposes movements in the rate of profit in the standard manner of the Marxian-economics literature. It then shows that an alternative decomposition analysis reveals that the rate of profit fell mainly because employment increased too slowly in relationship to the accumulation of capital. This result implies that Marx’s falling-rate-of-profit theory fits the facts remarkably well. The chapter concludes with a discussion of depreciation due to obsolescence (“moral depreciation”). It shows that the information-technology revolution has caused such depreciation to increase substantially and that this has significantly affected the measured rate of profit. The rates of profit discussed in Chapter 5 and prior sections of Chapter 7 would have fallen even more if they had employed Marx’s concept of depreciation instead of the U.S. government’s concept.

Chapter 8: Examines underconsumptionist theory, which has become increasingly popular since the recent crisis. Contrary to what underconsumptionist authors contend, U.S. workers are paid more now, in inflation-adjusted terms, than they were paid a few decades ago, and their share of the nation’s income has not fallen. The rest of this chapter criticizes the underconsumptionist theory of crisis. In particular, it argues that the underconsumptionist theory presented in Baran and Sweezy’s influential Monopoly Capital rests on an elemental logical error.

Chapter 9: Discusses what is to be undone. It argues that the U.S. government’s response to the crisis constitutes a new manifestation of state-capitalism, and it critically examines policy proposals based on the belief that greater state regulation, control, or ownership can put capitalism on a stable path. It then discusses the political implications of underconsumptionism and critique its view that redistribution of income would stabilize capitalism. Finally, it takes up the difficult question of whether a socialist alternative to capitalism is possible. Although the author does not believe that he has “the answer,” he addresses the question because he believes that the collapse of the U.S.SR. and the latest crisis have made the search for an answer our most important task. . |